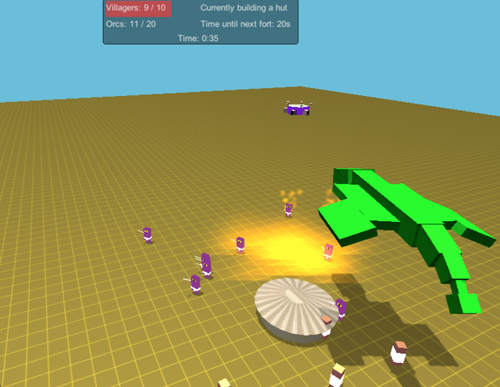

My goal was to finish Our Man Dragon in February, and I did so with 52 minutes to spare!

Obviously it’s still rough around the edges and isn’t the most attractive thing, but I completed all the major features I planned.

My goal in finishing this was to learn the ropes in each major feature of making a game. Short of sound effects, visuals, and controller input, I did just that.

In order to make a complete game I am proud of, it isn’t enough to have interesting gameplay. I need to at least hack together compelling music or visuals. If I am ever to make something I am proud of, I can probably afford a professional for one of those two, but not both.

It’s been awhile since I’ve provided an update on Our Man Dragon, so allow me to rectify that.

It’s not uncommon for software projects to spend just as much time going from “start” to “basically done” as they do to go from “basically done” to “done.” Our Man Dragon is no different - the basic gameplay was hammered out in a day while I am on month two of “finishing up.”

However, it’s dramatically more challenging to stay motivated towards the end of this game than the many non-game software projects in my career. The crux is that all of my work is now towards making sure a new player knows what they are supposed to do as well as I do. This means GUIs, intro screens, etc.

It feels tedious, but this is important work. Even though this is not a particularly fun game, I want it to be a complete game so that I have experienced each part of releasing a game. This has always been a learning project so I am determined to finish this before moving on to something more interesting.

For the curious, you can track my remaining work on the Our Man Dragon Trello board.

SP

Here’s roughly where I start in determining how much I like a game:

(average number of hard decisions per minute)/(number of pages in rulebook * number of times that players ask "Whose turn is it right now?”)

This metric favors a few types of games quite strongly:

There’s also a number of mechanics and genres that do extremely poorly. Random, chaotic games like Munchkin and Fluxx tend to provide few hard decisions. Interaction-light Euro-style board games like Agricola and Puerto Rico often result in an extraordinary number of “Whose turn is it?” questions because of the analysis required of players. Most wargames fail spectacularly because of their many rules and long turns.

If you have a similar rule of thumb or common theme in your gaming interests, I’d love to hear it.

The Tumblr One Terabyte of Kilobyte Age is my new obsession. The Tumblr is a snapshot of archived Geocities pages in chronological order. I’ve posted some of the more interesting below.

The blog of the research project taking these screenshots is fascinating as well. It captures a time when hordes of new users were trying to create on the internet. What strikes me is not how many are clearly unfamiliar with the “how” of creating their own homepages, but also with the “why”. This archive is littered with people writing statements to the effect of “I don’t know why I am doing this and don’t have anything to say, but…”

Definitely check it out.

“Worker Placement” in board gaming dates back to roughly the turn of the century, but recently there has been a second wave of games experimenting within the mechanic. Keyflower is the most ambitious of these that I have played. While I found the whole lesser than the sum of its parts, it has some rather clever ideas that I want to celebrate.

Keyflower is a game of building villages using workers to acquire and use a number of different building tiles. Your workers are both what you spend to activate buildings (placing them on a tile) as well as acquire buildings (placing them next to a tile). Each building is unique and provides its own unique, mathy perk.

It’s a clever game, but is burdensome to play. The sheer number of options demands careful analysis at all times, but the high degree of randomness in the draw of tiles and the play of others means it is challenging to most to do most of that analysis in advance of your turn.

That’s all nerd talk for saying it’s slow. Very slow. “People leaving the table entirely between their turns” slow. The slogan (slowgan?) of this game should be “Whose turn is it again?”

HOWEVER, that doesn’t make the game any less clever, and I want to call out a couple of the most cleverest bits.

In the game’s final round, you are buying tiles not because they do anything (they largely don’t), but because they establish victory conditions for you alone if you win the bid. This itself is immensely clever, but it gets better.

Each player is dealt a number of these tiles at the start of the game. Before the final round, they choose how many to make available for bidding. If I see Fred has a ton of ore on his tiles, then I may choose to keep the “5 VP for each 3 Resources” tile off the board at the end. However, perhaps I’ve also invested heavily in resources as well, at which point I have a tough (but unfortunately math-intense) decision ahead of me.

This ability to change the rules of victory is extremely clever, something I haven’t seen before in a game. Hidden information in games isn’t particularly new, but the uncertainty involved in it with Keyflower turns this concept on its head. It was absolutely thrilling to see this play out.

Workers come in four different colors. In of themselves, the colors are meaningless. A yellow worker can mine ore just as well as a red or green one. BUT WAIT! As with most things in Keyflower, there’s a twist.

Once I bid on a tile with a particular color, only workers of that color can be used to outbid me. Similarly, when I activate a tile, only workers of that same color can re-activate it. So while these workers have no absolute difference between them, they take on stark relative differences between each other.

It’s a very interesting way to play with the idea of currency. It’s as if I could place the first bid on an eBay auction in Confederate scrip and block anyone else from bidding against me. I’ve never seen a game that divorced the concept of currencies from cost in such a way.

Keyflower isn’t my favorite game and it isn’t one I will bring to the table often. Don’t think you shouldn’t try it though. It’s like a David Lynch movie - I’m glad I saw it even if I didn’t enjoy watching it.

Anyone truly interested in new board gaming concepts should play through a game of Keyflower - there’s several more I am sure I’ve missed. It may not be the greatest, but I’ll be damned if I didn’t end the game with my head spinning of ways those mechanics could be reused and reimagined.